Sitting in a medical clinic recently, as a young-looking nurse extracted blood from his veins, your columnist’s mind turned to the flexibility of the American labour market. How long, exactly, had she been on the job? The somewhat shocking answer: it was her first month. Six weeks of training was all it took, she explained, to make the transition from eyelash technician to phlebotomist, which offered higher pay and better hours.

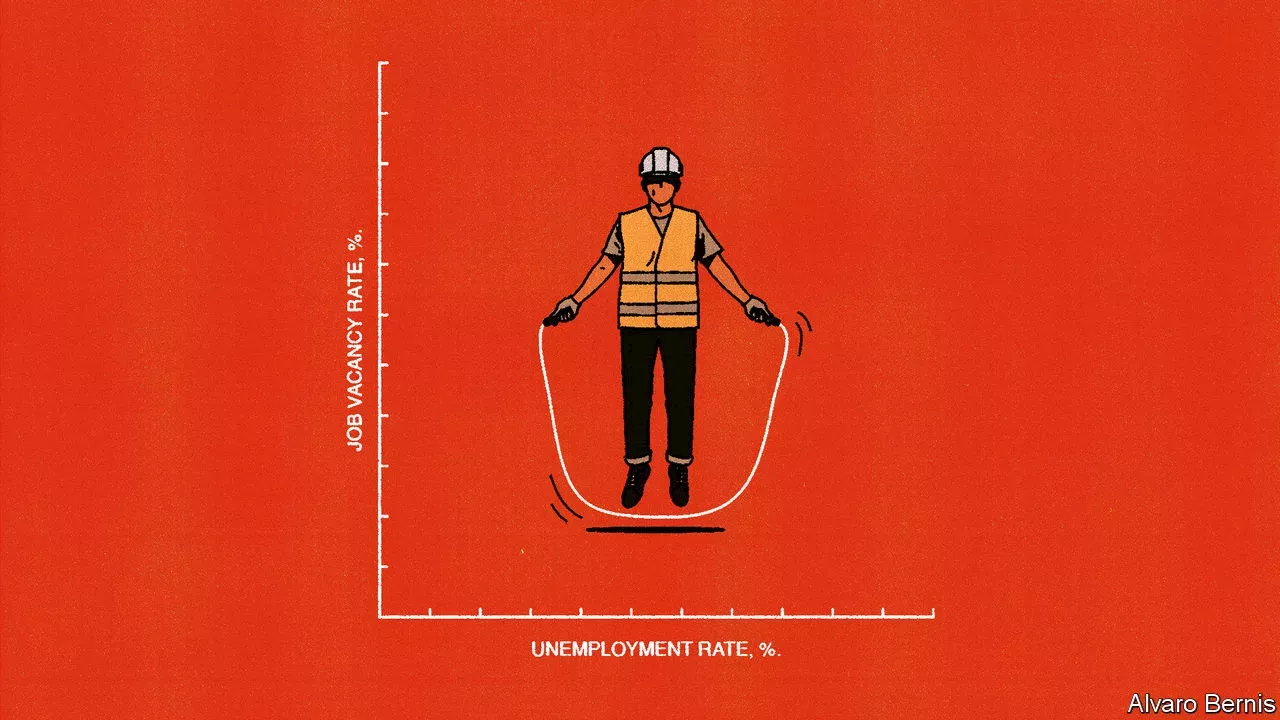

The typical explanation is that the willingness mismatch has abated: Americans have re-entered the labour force, while companies have cut their help-wanted advertisements. Question everything That, at least, is the conventional story. But think about it for a second and it is does not sit quite right. After all, the Beveridge curve is supposed to depict the state of the labour market. If, however, the curve itself is liable to move around, as this story suggests, it surely cannot be of much use.